15 February 2016

Has the regulator left banks and insurers living in fear?

When the UK financial markets went into meltdown in 2008, resulting in several banks being bailed out by the government, people were quick to point the finger at the regulator - and rightly so. One of the main jobs of any financial regulator must be to prevent companies from harming their customers. Yet, there we were with savers' money evaporating from within their Icelandic bank accounts, just months after Northern Rock had come within a whisker of going bust. Why had the regulator not seen any of this coming? Why were there not protections in place to ensure that customers' money could not evaporate?

When the Coalition government came into power in 2010, one of the first things it did was to rethink the regulatory framework that oversees our financial services industry. I was sceptical that these changes would be anything more than cosmetic, but I was happy to be proved wrong. The Financial Conduct Authority has been much more proactive than its predecessor, the Financial Services Authority. Problems have been spotted before they have blown up into something more serious - and retrospective punishment for companies that have stepped out of line has been harsher.

This is the right response. There's no point in having rules at all if they're not enforced properly, or the penalties for breaking them are not stern enough.

The regulation of punctuation?

But one of the less attractive side effects of having a more effective regulator is that many firms have gone too far in their attempts to come up with processes that comply with the rulebook. Fear of being called out for stepping out of line has led companies to ever more extreme lengths to please the FCA.

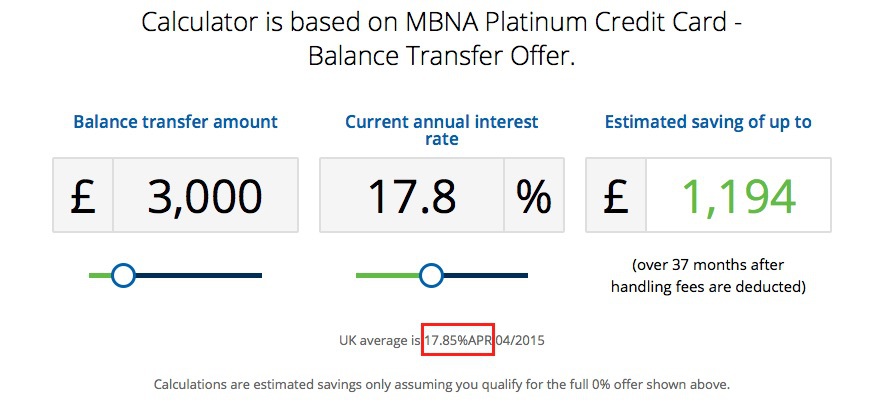

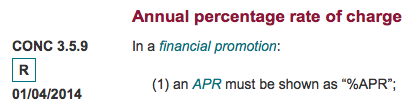

I came across a new and particularly absurd example of this last month. Take a look at any mention of APR on the MBNA website, and you'll see that it's always written as "%APR" - without a space between the % sign and the letters APR. A typo, perhaps? Sadly not.

MBNA very delibately misses out the space, because of a line in the FCA credit rulebook (CONC 3.5.9 in case you're interested), which states that "In a financial promotion, the APR must be shown as '%APR'".

The onset of super-compliance

This example may be trivial (not to mention comical), but there are an increasing number of incidents in other sectors which demonstrate that companies are losing the ability to keep the rulebook in any kind of perspective.

I recently went through the application process for a new mortgage - the first time I'd done so since the Mortgage Market Review (MMR) rules came into force in 2014. To say that the application process was arduous would be a massive understatement. As well as an initial half hour call followed by requests for multiple pieces of information, I was eventually forced to sit through a two-hour advice call.

The additional borrowing was going to lower my monthly outgoings, and leave me with a loan to value of less than 60% on my mortgage. Yet, I was treated as though I was taking a massive risk - and may prove to be a massive risk for my lender.

The MMR rules were designed to ensure that lenders check that borrowers can afford what they're borrowing. And that's quite right. But the application of the rules by many lenders is completely over the top.

During my mortgage advice call, I was persuaded to change my mind and opt for a fixed rate deal rather than a tracker. After that, the call handler repeated back to me - at least 10 times I think - something along the lines of "OK, so just to confirm, you originally wanted to go for a tracker, but when you noticed that the difference in price was small, you decided to go for a fixed rate to give yourself the extra security". By the time she'd said it five or six times, I was thinking about changing my mind again.

It goes without saying that I'd rather see companies err on the side of caution when they're building processes to protect consumers. But there has to be some proportionality and room for common sense.

Super-compliance is a worry as it suggests companies are acting as robots, and are failing to treat their customers as individuals. It may be challenging to personalise your customer experience when you're dealing with hundreds, even thousands, of people every day. But it must be possible in this day and age. And if banks and insurers are to rebuild trust with their customers, tailoring processes to their individual needs, and looking beyond box-ticking, is crucial.