27 November 2017

The Fairer Finance guide to simple writing

This year we’ve awarded our Clear & Simple Mark for the very first time. Documents ranging from Back Me Up’s policy booklet to Co-op’s funeral plan terms and conditions have achieved the high standards of our award.

We established the award to recognise providers that have made their terms clear and understandable.

According to the National Literacy Trust, 5.2 million adults in the UK have a reading age of 11. But these documents often have a reading age that’s twice as high.

Here we set out the key things we look at in our analysis - and what providers can do to stand a chance of passing it.

Reading Grade

The first port of call when analysing readability is to find out a document’s reading grade. This is a numerical measure of how simple the structure of the language is. The higher the number, the more difficult it is to read.

We use the Automated Readability Index (ARI) to manually analyse the documents we review. It is the most reliable and up-to-date of the major readability formulas, according to research by the US government.

It uses the number of letters, words, and sentences to create a picture of average word and sentence length. Keep these averages low, and the reading grade should be low as well.

Words per sentence is particularly important here. Some long words are unavoidable – but long sentences are not. We’ve analysed documents containing sentences that are triple figures in length.

Sentences should be around 17 words long on average. Try reducing sentences down to single clauses to achieve this.

Doing this should bring the average words per sentence down – which will go a long way to reducing the reading grade.

Jargon

It is not just the structure of the language, but also the word choice that affects readability. Jargon can dramatically reduce reader comprehension, and there are many types that we look at. Financial jargon, legal jargon, and ‘common’ jargon all need to be kept to a minimum.

Financial jargon refers to the terminology of the industry, such as acronyms like ‘CHAPS’, or terms like ‘creditor’. Some of these terms are unavoidable due to the nature of the documents. If they cannot be replaced with more common words, then they must be clearly explained.

Legal jargon can refer to Acts of Parliament. Acts are commonly used in financial documents – but the average consumer doesn’t know what they mean. Some acts, such as the Consumer Credit Act 1974, need to be included. If so, they must be explained.

But there are many that don’t need to be in there. For example, Danske Bank’s current account terms and conditions contains 3 Acts of Parliament, while HSBC’s has none.

Legal jargon can also refer to specific terminology. Terms such as ‘whereto’ and ‘hereunder’ are never used outside of these documents - and there is no good reason to use these terms inside them either.

The final type of jargon we look at is what we call ‘common’ jargon. These are words that have a simpler replacement. For example, ‘terminate’ can be replaced with ‘end’. ‘Diminish’ could be replaced with ‘reduce’.

As George Orwell said, “never use a long word when a short one will do.”

Headers

To make these documents readable, they must also be easy to navigate.

The reader approaches these documents like manuals, not novels. They will often have a certain question they need answering. Therefore, headers must be simple and descriptive.

We recommend making headers rhetorical where possible. For example, “the claims process” could be rewritten as “how do I make a claim?”. Equally, “arrangements regarding arrears” could be rewritten as “what happens if I miss a payment?”.

Inter-referencing

Financial documents tend to reference clauses from other parts of the document. We call this ‘inter-referencing’. An example of this would be “in accordance with applicable laws for the purposes outlined in clause 1.5 above”.

This disrupts the flow of the document, and gets in the way of reader understanding.

When we rewrite documents, we look to not just change the language but also the structure. It is far better to get all terms applicable to a section contained within that section.

It is also difficult to write in a conversational way if the document is segmented into numbered clauses. Documents written like this read as a compliance checklist. They should instead be a means of explaining the product to the customer.

Conversational Tone

It’s not just the complexity of language that can put readers off – it’s also the tone. Often these documents are written in a way that makes no attempt to engage the reader.

Writing in a conversational way that addresses the reader directly has been shown to improve readability. Although it’s tempting to draw terms and conditions out as formal legal documents, often an informal approach is more effective.

For example, “the policy number is a requirement of the claim making process and must be kept secure” could be rewritten as: “if you are unfortunate enough to have an accident, you’ll need your policy number to make a claim. So it’s really important that you keep this safe”.

Word count

Our Spare Us the Small Print campaign has often pointed out how ridiculously long financial documents can be.

We’ve analysed documents that are twice as long as Orwell’s Animal Farm. We’ve seen providers explain their terms in 30,000 words - and others explaining an almost identical product in only 7,000 words.

Cutting down the overall word count will do wonders for reader understanding. Often these extra words are terms mentioned above – unnecessary uses of ‘hereunder’, or Acts of Parliament.

Also, the longer the sentence the greater the use of conjunctions and other such words. Splitting sentences out should help cut the word count.

But be careful here – often we’ve rewritten documents and had to use a greater number of words to explain certain features. Less is not necessarily more. But cutting out the terms described above should cause the word count to fall overall.

Examples

Because financial documents contain a range of numerical information, examples are often an effective way of explaining them. Concrete language is always better than abstract terms.

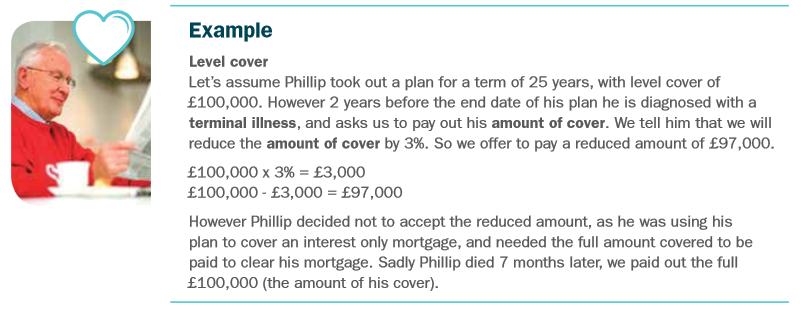

This example from LV’s life insurance document is a good indication of how to get this right. Notice that conversational, concrete language is mixed with numerical calculations – greatly enhancing reader understanding.

Conclusions

Hopefully this should provide some handy advice for anyone looking to improve the readability of their documents. We’ve got one final tip – which you may have picked up on already. We’re not sticklers for grammar.

We believe language evolves, and mirroring everyday language is a great boost to readability.

So, if you think your document can pass our test, then please send it over. We want to see all financial documents written clearly and simply. There’s no good reason why they shouldn’t be.